For the second time in just months, Baku has warned its citizens against traveling to Iran in the wake of a deadly attack on the Azerbaijani Embassy in Tehran in January that it blamed on the “unstable situation in the Islamic republic.”

In what has become a habit in recent weeks, Iranian officials have been angered over the perceived obstinacy of its northwestern neighbor and the encroachment of regional adversaries on what Tehran believes to be its backyard.

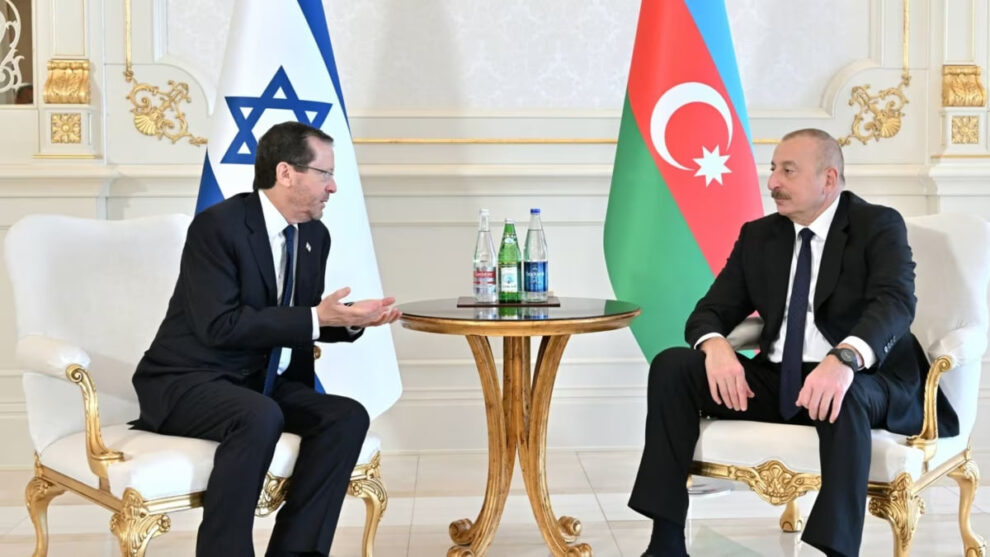

Azerbaijan’s increasingly cozy relations with Iran’s archfoe, Israel — highlighted by defense deals, the opening of an embassy in Tel Aviv in March, and Israeli President Isaac Herzog’s first visit to Azerbaijan last month — has become a reliable trigger for Tehran as its own ties with Baku hit new lows.

Tehran does not officially recognize Israel, which it refers to disparagingly as a Palestinian-killing “Zionist regime” and accuses of having designs on sabotage and unrest within Iran’s borders.

“The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Azerbaijan has warned against the travel of its citizens to Iran! This is the same policy that the president of the fake, child-killing, and occupying Zionist regime took during his recent trip to Baku,” Iranian Foreign Ministry spokesman Nasser Kanaani tweeted on June 5. “What should scare the people of Azerbaijan is the Zionist regime, not civilized and Islamic Iran.”

Complicated Relationship

Herzog’s visit, during which he said he and Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev discussed in depth “the regional security structure that is threatened by Iran,” appeared to have struck a nerve in Tehran.

“From the standpoint of the Islamic republic, the close relations of Azerbaijan with Israel is a major problem, [as is] the active presence of Israel in the military sphere [of Azerbaijan] and providing it with weaponry and the tight economic and security ties between the two countries,” Iran analyst Touraj Atabaki, professor emeritus and chairman of the social history of the Middle East and Central Asia at Leiden University, told RFE/RL’s Radio Farda.

But Baku’s budding ties with Israel are just one among many factors straining Iran’s relationship with Azerbaijan, a fellow Shi’a-majority country.

Observers say the relationship has been complicated ever since Azerbaijan became independent from the Soviet Union in 1991. But things became even more problematic when Baku retook territory along Iran’s border during its 2020 war with Armenia over Nagorno-Karabakh.

While Tehran supported Azerbaijan’s claim to territory occupied by Iranian ally Armenia, it has strongly opposed Baku’s intention to use the retaken lands to build the east-west Zangezur Corridor, which would connect mainland Azerbaijan to its Naxcivan exclave and open a long-sought trade route to Tehran’s rival, Turkey, and beyond.

The plan was boosted by the Russian-brokered cease-fire that ended the war over Nagorno-Karabakh and called for “all economic and transport connections in the region to be unblocked.”

While Iran launched large-scale military exercises dubbed “Mighty Iran” along its border with Naxcivan in October 2022 — a show of force to underscore that it would not “permit the blockage” of its trade and transport links to Armenia — the initiative has moved forward.

As talk of a possible peace deal between Armenia and Azerbaijan pick up steam, Russian Deputy Prime Minister Aleksei Overchuk announced on May 31 that the two sides were close to an agreement that would pave the way for the route through Armenia and Azerbaijani territory previously occupied by Yerevan, and “open the road to Russia, the countries of the European Union, and Iran.”

As Iran seeks to boost its sanctions-circumventing trade with Russia, including with the completion of a second north-south route that would also pass through Azerbaijan, the prospect of seeing a trade route crossing its passage to Armenia remains a serious bone of contention.

“Iran doesn’t like this corridor because in the larger competition and struggle between Tehran and Baku it weakens Iran if this corridor is created, because right now Azerbaijan has to use Iranian airspace or territory to resupply Naxcivan,” said Luke Coffey, a foreign policy expert at the Washington-based Hudson Institute think tank.

The Zangezur Corridor, if completed, would mean that “Iran will become less important in the eyes of policymakers in Baku, and perhaps Azerbaijan would feel emboldened to take a more hard line against Iran,” Coffey told RFE/RL.

‘Mighty Iran’ And Shi’ite Brotherhood

Such a scenario does not sit well with Iran, which has worked to exert its influence in Azerbaijan.

“A significant segment of the Azerbaijani population is Shi’a and since the creation of the independent Republic of Azerbaijan, the Islamic republic has considered Azerbaijan as the backyard for the [expansion] of the influence of its brand of Shi’ism,” Atabaki said.

Tehran is also wary of the effects the loss of influence on Baku will have on Iran’s large ethnic Azeri population, separated from Azerbaijan by the Aras River and located primarily in Iran’s East and West Azerbaijan provinces.

During the 2020 war over Nagorno-Karabakh, Coffey said, images emerged on social media of ethnic Azeris in Iran “waving Azerbaijani flags on the other side of the river, literally cheering on, like a spectator event, the advancements of the Azerbaijani armed forces.”

In November 2022, Baku stoked tensions with Iran by staging its own military exercises along the Iranian border, with Aliyev saying they were necessary to show Tehran that “we are not afraid of them.”

“We will do our best to protect the secular lifestyle of Azerbaijan and Azeris around the world, including in Iran,” Aliyev added. “They are part of our people.”

A Turning Point

Amid the continuing back and forth, the January attack on the Azerbaijani Embassy in Tehran was seen by some observers as a turning point in bilateral relations.

Azerbaijan evacuated its embassy staff following the January 27 attack, in which a security guard was killed and two others injured when a gunman stormed the complex and opened fire. Baku blamed the attack on the Iranian secret service and called it an “act of terrorism.”

In February, the Azerbaijani authorities said that they had detained nearly 40 people on suspicion of spying for Iran.

The fray worsened in March with the alleged assassination attempt on Fazil Mustafa, an Azerbaijani lawmaker who had been critical of Iran. Following the arrest in April of four people in connection with the incident, Baku accused Tehran of orchestrating the plot.

Two weeks later, Azerbaijani media reported the arrest of 20 people allegedly affiliated with Iran’s Intelligence Ministry who were accused of promoting “the Islamic republic’s propaganda, spreading religious superstitions, [and] attempting to overthrow the secular government of Baku.”

In a tit-for-tat move, Tehran and Baku expelled four of each other’s diplomats in April. And while diplomatic relations continued, the strains were evident as the two countries’ foreign ministers held a series of phone calls that month in which Iran made clear that Tehran did not approve of Baku’s relations with Israel.

“Only enemies benefit from the existence of differences” between the two countries, Iranian Foreign Minister Hossein Amir-Abdollahian was quoted as saying by Iran’s Shargh daily.

Iran’s vice president in charge of economic affairs, Mohsen Rezaei, went a step further while addressing members of the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC) in the western Lorestan Province.

“The incitement of the Republic of Azerbaijan and the signing of arms contracts between Israel and the Republic of Azerbaijan was aimed at creating riots in the north of Iran, and to shift the thinking and focus of the army, the IRGC and the government of Iran to the north so that Israel can bomb Iran’s nuclear sites,” Shargh quoted Rezaei as saying.

On May 16, the Azerbaijani authorities announced another haul of individuals it said were recruited by Iran to disrupt Azerbaijan’s constitutional order and establish Islamic law. This time, Baku claimed, the seven men detained had allegedly planned to assassinate Azerbaijani public figures.

The Feud Continues

That set the scene for the visit to Baku by Herzog in late May, held under strict security out of fear of Iranian retaliation.

After meeting Herzog, Aliyev lauded the boost that Israeli weaponry had given his country “to modernize our defense capability and allow us to defend our statehood, our national interests, and our territorial integrity.”

Nearly 70 percent of Azerbaijan’s arms imports between 2016 and 2020 were from Israel, according to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute.

Herzog, in his comments after meeting Aliyev, said that “we expect to develop cooperation between us in many fields.”

Iranian Foreign Ministry spokesman Kanaani again took to Twitter to air Tehran’s views on the development, writing on March 31 that “none of the regional moves of the Zionist regime remain hidden from the penetrating eyes of the Islamic Republic of Iran.”

The next day, an Iranian opposition hacking group released alleged classified Iranian government documents that appeared to shed light on the January embassy attack and indicated the need to reevaluate Tehran’s diplomatic ties with Azerbaijan.

The documents, purportedly distributed among top Iranian officials, included advice on how to distance Azerbaijani society from its government and attributed Baku’s policies to “Zionist” influence.

That potential bombshell was followed by Azerbaijan’s announcement on June 2 that it had closed Iran’s cultural attache office in Baku, citing “recent disagreements” between the two countries.

And on June 3 came the spark for Kanaani’s latest Twitter outburst: Azerbaijan’s renewed travel warning advising its citizens not to travel to Iran and for those who are already there to be vigilant.

Within seconds of blasting Azerbaijan and its ties with Israel in his first tweet on June 5, Kanaani took a softer line, writing that Iran would still “open our arms to our Azerbaijani brothers and sisters,” with the goal of continued “mutual respect and respect for neighborhood customs.”

But in his comments to Radio Farda on June 7, Iran expert Atabaki expressed skepticism, saying that “the Islamic republic is not planning to see its ties with Azerbaijan as an equal relationship.”

And that mindset, Atabaki said, had allowed relations to reach their current low.

Source: Radio Free Europe Radio Liberty